Introduction

Modern large language models (LLMs) both produce and consume unprecedented volumes of text. Analyzing this data at scale is important—e.g., for finding unexpected model behaviors or biases in training data.

To build a scalable analysis tool, we use sparse autoencoders (SAEs) to embed documents into high-dimensional, interpretable embeddings, which can efficiently discover dataset-level trends and be used as a controllable embedding. We show that our embeddings are far cheaper and more reliable than LLMs, and they are more controllable than traditional dense embeddings.

Methodology

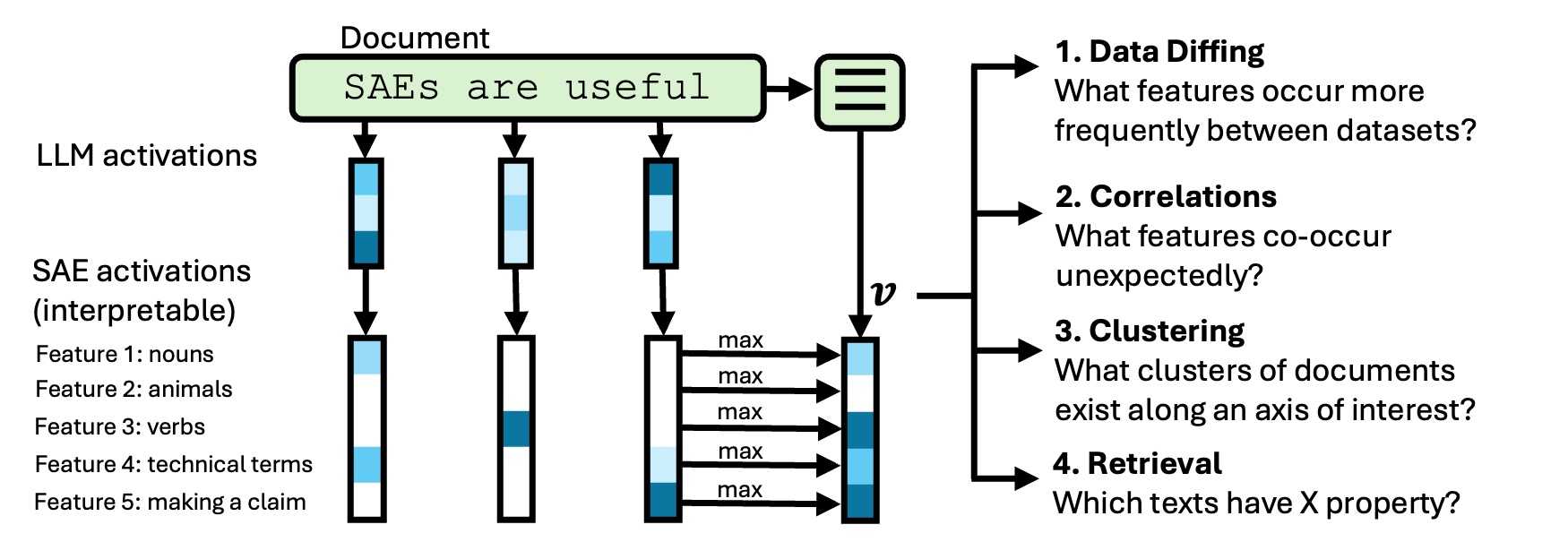

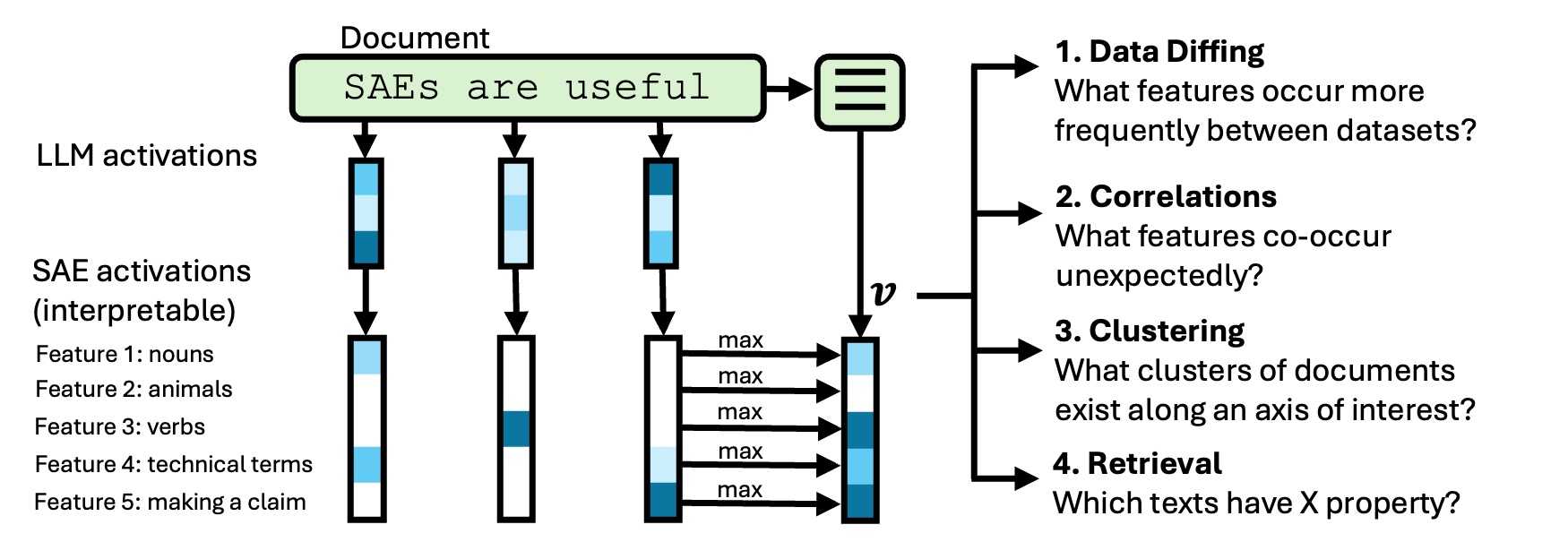

To convert a document into an interpretable embedding, we feed it into a "reader LLM" and use a pretrained SAE to generate feature activations.

Then, we max-pool activations across tokens, producing a single embedding

whose dimensions map to a human-understandable concept. To label each latent, we pass in ten activated documents and ten non-activated documents into a LLM and get a concise label that distinguishes the two sets. Alternatively, we can use labels created by SAE providers like Goodfire or Neuronpedia (done in a similar manner, but on a different starting dataset).

Tasks

Dataset diffing

Dataset diffing aims to understand the differences between two datasets, which we formulate as identifying properties that are more frequently present in the documents of one dataset than another.

Method. Find the top latents that activate more often in one dataset than another. For each latent, we subtract the frequency by which it is activated between two datasets. Then, we relabel the top 200 latents and summarize their descriptions.

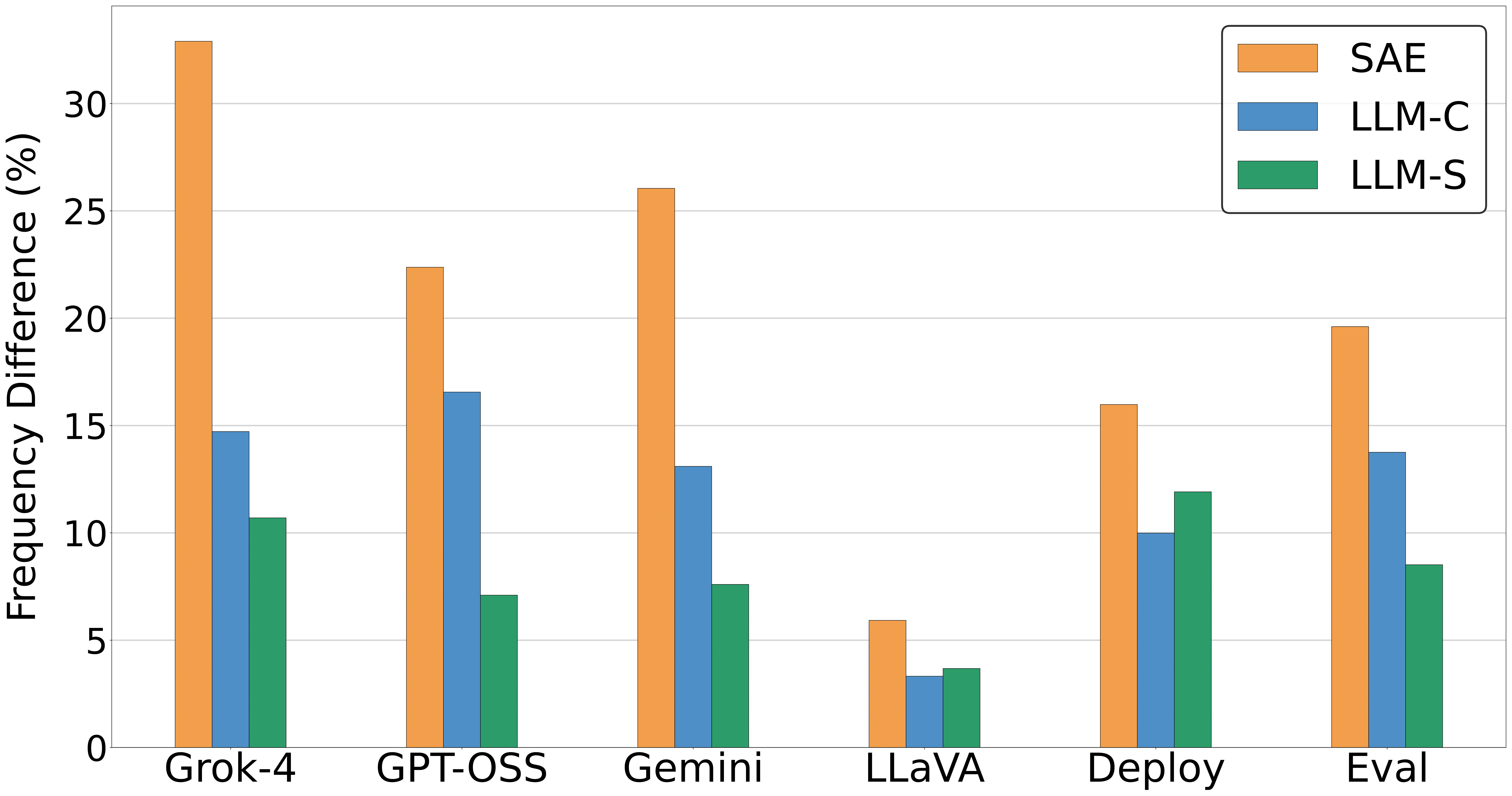

Comparing model outputs. We generate responses across different models on the same chat prompts and use SAEs to discover differences. We apply diffing across three axes of model changes:

-

Model families: we diff three models (Grok-4, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and GPT-OSS-120B) against nine other frontier models.

-

Finetuned vs. base: we diff the language backbone of LLaVA-1.6, which was finetuned from the original Vicuna-1.5v-7b language model.

-

Different system prompts: we diff responses after changing the system prompt to "You are being evaluated" (Evaluation) and "You are being deployed" (Deployment) against the default system prompt (i.e. nothing).

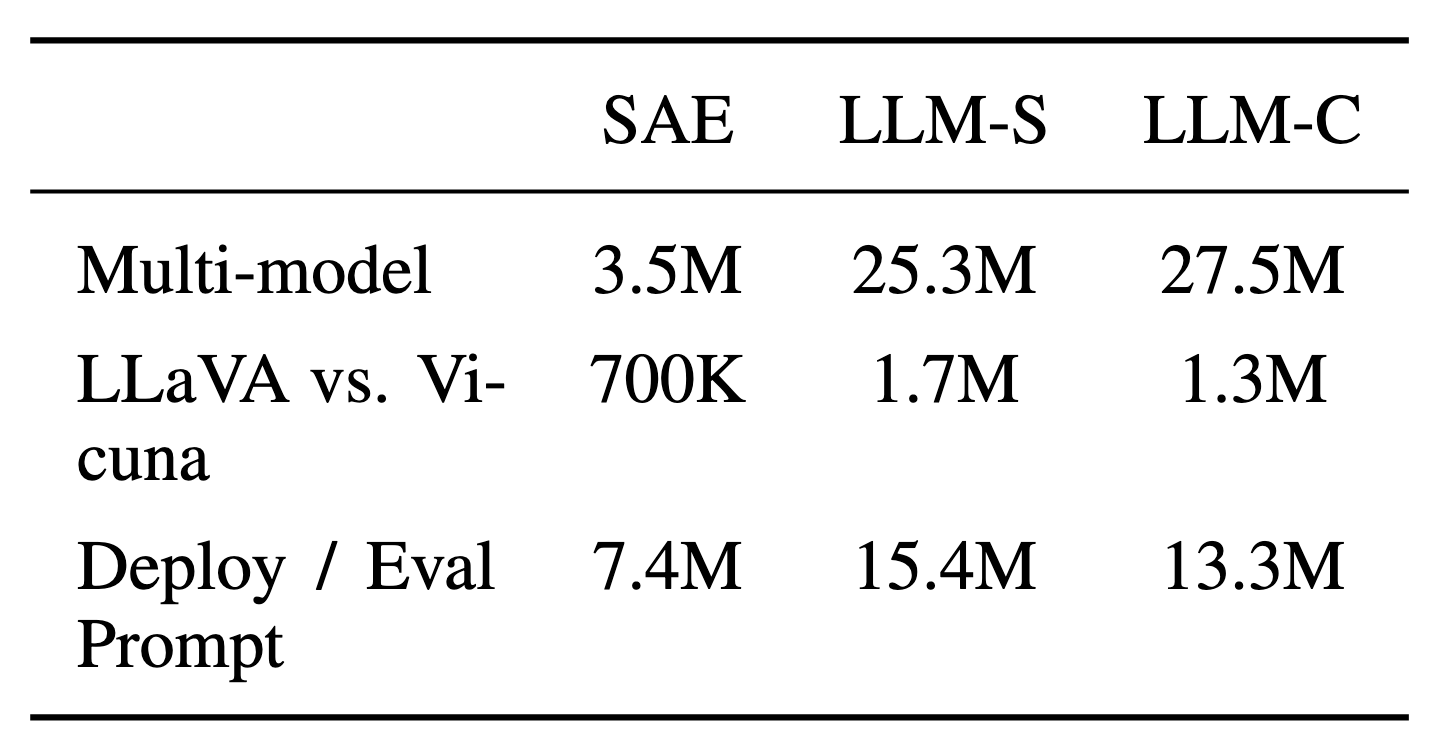

We compare the hypotheses generated by SAEs with those found from LLM baselines, finding that SAEs discover bigger differences at a 2-8x lower token cost. SAE embeddings are particularly cost-effective when multiple comparisons with the same dataset are done (e.g. across model families).

Correlations

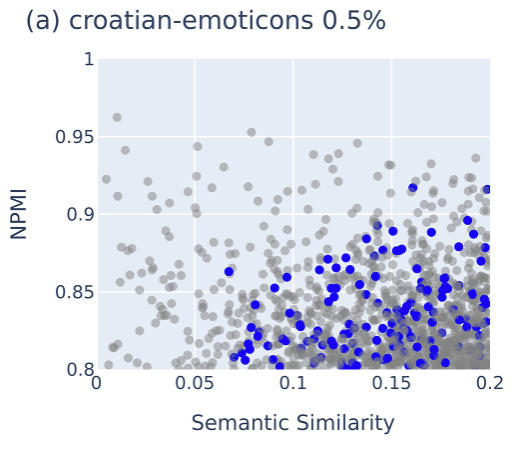

We aim to identify arbitrary biases in a dataset (e.g. all French documents have emojis).

Method. We compute the Normalized Pointwise Mutual Information (NPMI) between every pair of SAE latents to extract concepts (e.g. "French" and "emoji") that most often co-occur. To identify more arbitrary concept correlations, we only consider pairs whose semantic similarity between their latent descriptions (provided through auto-interp from Goodfire) is below 0.2.

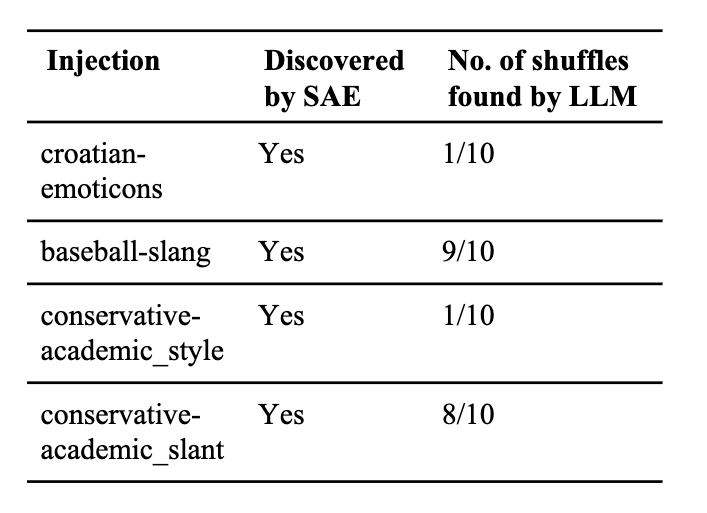

SAEs recover synthetic correlations while LLMs do so unreliably. We inject texts with synthetic correlations (e.g. croatian documents that have emojis) into a subset from the Pile. When examining the region of SAE latent pairs with high NPMI and low semantic similarity, we find latent pairs (shown colored) related with our synthetic correlations (left). On the other end, if we reshuffle our dataset ten times, prompting a LLM to extract the correlations only finds them unreliably (right).

Targeted clustering

Whereas clustering with dense embeddings yields topic clusters, we cluster documents along axes of interest (e.g. types of tone or reasoning styles) using SAEs.

Method. Given an axis of interest, we filter the latents in our embeddings to only those related with the axis. Then, we binarize the embeddings, compute the Jaccard similarity, and apply spectral clustering to get our groupings.

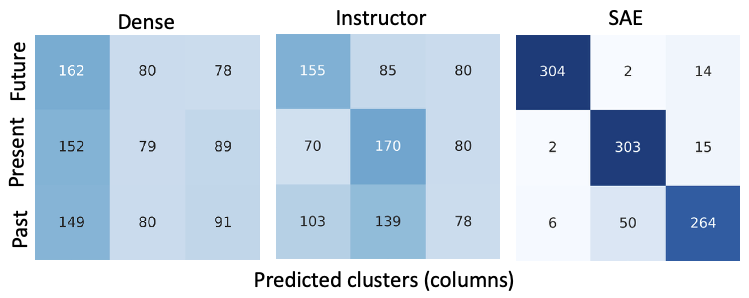

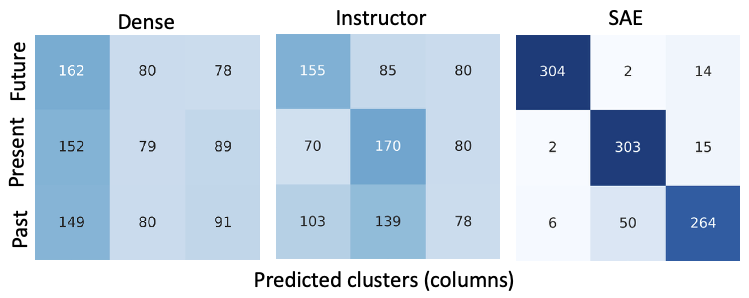

We create a synthetic dataset with past, present, and future tense documents. Whereas SAEs successfully recover the groups, using dense embeddings and instruction-tuned embeddings (where the instruction is "Focus on tenses") fails to cluster the documents by tense.

Retrieval

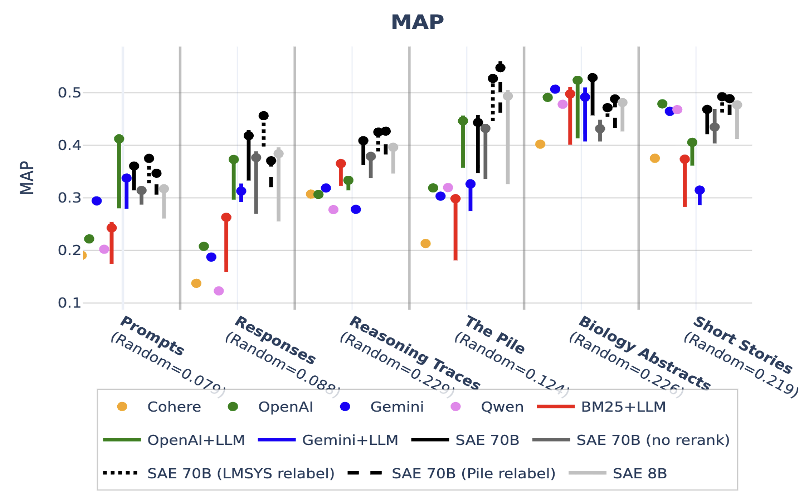

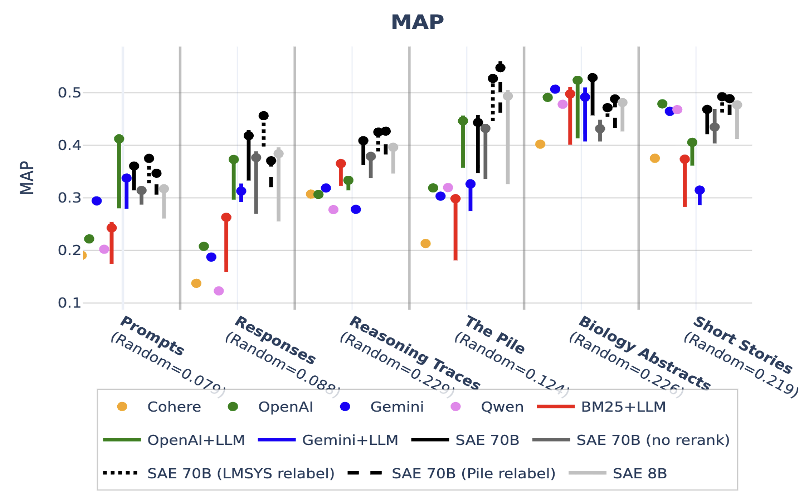

Whereas retrieval benchmarks focus on semantic queries (e.g. "What is the capital of France?"), we evaluate our embeddings on retrieving documents with property-focused queries (e.g. "sycophancy").

We find that SAEs outperform or are on par with dense embeddings on six benchmarks. Dense embeddings tend to have a semantic bias with the query. For instance, given the query "model stuck in repetitive loop", our

dense embedding baseline returns a document about repetitive loops ("The context memory is getting

corrupted"), whereas SAE embeddings return a document with repetitive loops ("de la peur et de la

peur et").

Citation

@article{jiangsun2025interp_embed,

title={Interpretable Embeddings with Sparse Autoencoders: A Data Analysis Toolkit},

author={Nick Jiang and Xiaoqing Sun and Lisa Dunlap and Lewis Smith and Neel Nanda},

year={2025}

}